Waldorf News

Waldorf Education in Public Schools: Educators adopt—and adapt—this developmental, arts-rich approach

In the quest to fix ailing schools, should we slow down to move faster?

Just as the handmade, home-farmed foodie movement is transforming how consumers view processed food, is education’s equivalent—Waldorf-style schooling that favors hands-on art and personal exploration while shunning textbooks and technology—just what school reform needs?

It sounds counterintuitive for struggling students to spend class time on, say, knitting and drawing. Yet, a small but growing number of public schools are embracing Waldorf methods in hopes of engaging students in ways advocates say traditional approaches do not—and raising test scores along the way.

Once a private school model chosen by mostly middle- and upper-middle-class families for its child-centered, developmental approach to schooling, the number of Waldorf-inspired public schools has risen quickly, from a dozen in 2000 to 45 in 2010, with another 30 expected to open this year, according to the Alliance for Public Waldorf Education, a non-profit membership group for public Waldorf schools. Many are charter schools.

“A lot of parents and educators are recognizing that what we are doing in traditional education is not working for kids,” says Caleb Buckley, board president of the alliance and director of the Yuba River Charter School. Founded in Nevada City, Calif., in 1994, Yuba River was the first public Waldorf charter school to open in the United States.

While most Waldorf schools are elementaries, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation helped launch the first public Waldorf high school four years ago at the George Washington Carver School of Arts and Science in Sacramento, Calif., replacing a failed America’s Choice program in the building. Test scores have since risen dramatically: In 2008, 67 percent of 11th-graders scored “far below basic” or “below basic” in English; in 2011, just 12 percent did. Teachers are happier as well, says principal Allegra Allesandri. While many teachers spent the summer boning up on content, Allesandri’s teachers also honed skills in bookbinding, painting, and felting. Many Carver faculty gatherings include singing in harmony and playing games. “Those skills, which might be about singing, are also about working together successfully,” she says.

Ida Oberman, author of The Waldorf Movement in Education from European Cradle to American Crucible 1919–2008, is so convinced that Waldorf holds answers for urban school reform that in August she launched a Waldorf-inspired school of her own: the Community School for Creative Education in nearby Oakland, Calif.

“We know about the achievement gap but haven’t figured out how to close it,” insists Oberman. She says pressure to raise test scores in poor, underperforming districts has led to a narrowing of curriculum, leaving students who may lack rich home environments with even less to engage them. “No Child Left Behind has failed,” she says, asking, “What do we do to keep the children in this system, learning and growing?”

“Head, Heart, Hands”

While Waldorf education as conceived in 1919 by Austrian philosopher Rudolf Steiner brought a Christian and spiritual bent to developmental learning, U.S. schools have focused more on its pedagogical methods. Waldorf teachers use an experiential, arts-rich approach—“a head, heart, hands” philosophy—that includes singing, reciting poems and stories, and handwork, from weaving to woodwork.

Waldorf education, which often requires families to limit TV watching and electronics at home, considers a child’s growth to take place in three seven-year stages from birth to age 21. Each stage is characterized by developmental phases—imitation, imagination, and the search for truth—that inform curriculum. The goal is to match learning with natural development, spurring a kind of organic compounding of children’s innate drive to make sense of their worlds.

In early grades, strict Waldorf classrooms delay overt academic work in favor of imaginative play and movement centered on myths and fairy tales. Multiplication tables, for example, are not taught until fourth grade, although kindergarteners may gain early math skills as they knit. Even high school students studying science find a narrative focus as a teacher describes how Charles Darwin struggled to conceive his theory of evolution. Students may draw muscle cells to learn about them. There are no textbooks; students create their own “lesson books” to chart their learning.

In early grades, strict Waldorf classrooms delay overt academic work in favor of imaginative play and movement centered on myths and fairy tales. Multiplication tables, for example, are not taught until fourth grade, although kindergarteners may gain early math skills as they knit. Even high school students studying science find a narrative focus as a teacher describes how Charles Darwin struggled to conceive his theory of evolution. Students may draw muscle cells to learn about them. There are no textbooks; students create their own “lesson books” to chart their learning.

Waldorf also emphasizes strong teacher-student relationships. Ideally, teachers stay with the same class for the first eight years, a practice known as looping. The daily schedule has an extended Main Lesson, which may last two hours. But before academics commence, each student is greeted by name by the teacher and joins in whole-class movement and singing.

Not surprisingly, Waldorf has been on the educational fringe. “In the public sector, Waldorf has been seen as loosey-goosey, weird, or even cultish,” says Oberman, whose charter application was first rejected. “It’s taken some real case building.”

A Long View of Education

Authentic Waldorf education doesn’t dovetail neatly with American public schooling. There is Steiner’s Christian focus as well as the seeming indifference to metrics and assessment data. For public Waldorf schools, expunging Christian images and celebrations like passion plays has been straightforward. The tougher challenge is to show that kids are learning. Waldorf educators have such a long view of educating children and building capacities that, even by high school, students taking SATs at traditional Waldorfs “do all right, but considering they are in private schools, it’s nothing to write home about,” says Eugene Schwartz, educational consultant to public and private Waldorf schools.

There is little independent research on Waldorf outcomes. A 2001 study by Jennifer Schieffer and R. T. Busse compared test data in 1997–1998 and 1998–1999 among poor fourth-graders in two schools, one a public Waldorf and one a traditional public school, and found that Waldorf students scored somewhat better.

In 1997, Oberman considered survey data from 500 Waldorf grads, Gates Foundation documentation, and test scores from four public Waldorf-inspired schools. Survey data show Waldorf grads watch less TV and spend more time with friends and in creative pursuits, which is not surprising. But Oberman did identify a notable pattern: Waldorf students score below district peers in the early grades—and then catch up.

For example, at the Woodland Star Charter School in Sonoma County, Calif., test scores for 2010 show a stunning 81 percent of the second-graders scoring “below basic” or “far below basic,” compared with 32 percent of district peers. By eighth grade, however, none of the school’s students score in that level (in fact 89 percent are “proficient” or “advanced”), while 19 percent of district peers score in the lowest two levels and just 56 percent in the top two levels. Results have been less dramatic at some Waldorf-inspired charters, whose students in upper grades have scored about the same as district peers.

Making Waldorf Work

Increasingly, however, there is less waiting and more action as public Waldorf leaders, aware that poor scores can threaten their existence, alter approaches to improve test results (see sidebar “Adapting Waldorf in Rural Hawaii”).

Adapting Waldorf in Rural Hawaii

With new fifth-graders coming in one or two grade levels behind in reading, Chris Hecht, founder and executive director of the Kona Pacific Public Charter School in Kealakekua, Hawaii, did something un-Waldorf at this Waldorf school: He added extra academic periods plus a schoolwide half-hour reading time.

How to make it Waldorf? “We pick a lot of classic reading texts, fairy tales, and stories with morals for the children,” he says, in order to feed a passion for reading and learning into adulthood.

Located in a poor, rural, agricultural community, the school has also adopted the Waldorf tradition of looping so that each student has the same teacher throughout his or her elementary years.

Located in a poor, rural, agricultural community, the school has also adopted the Waldorf tradition of looping so that each student has the same teacher throughout his or her elementary years.

“What really underlies Waldorf education is a perspective on human development,” Hecht says, adding that it does not have to have “a specific look or feel.”

When test scores dropped at the Waldorf-inspired Novato Charter School in California, for instance, the district superintendent came right to the point, recalls Rachael Bishop, the school’s director. “She said, ‘You have to come up 45 points by next year. No pressure.’”

Bishop, trained as a public school administrator, pulled out binders of state standards, to the dismay of her staff. What began with denial and pushback from faculty, however, turned into a realization that what they already did fit standards, she says; they just needed to be more explicit. For example, second-graders who were making their own pentagons for a class exercise weren’t being taught the word “pentagon” in a way that they would recognize the word on the state tests. “We know the pentagon will be on the second-grade test,” she says, “so now the teacher will write ‘pentagon’ on the board, and the kids get to the test and say, ‘Oh I’ve seen that before.’ ”

Their efforts worked. Scores rose 91 points. But Bishop has kept at it, seeking to raise middle school math scores by doing the sacrosanct: buying textbooks. They still do project-based activities, start class with a verse perhaps by Albert Einstein, and end by thanking the teacher. But Bishop says the texts and 40-minute daily math lessons “look more like public school.”

Reform Challenge: Oakland

It’s one thing to tweak Waldorf methods in suburban Novato and another to lean on Waldorf in districts where students may be behind academically. Oberman, whose school just opened with 103 children in grades K–3 in six classrooms of the Howard Elementary School in Oakland, has the added challenge of serving an immigrant population. English is not the primary language spoken at home, and because many are extremely poor, she says, they are also transient.

“We are adjusting more radically than many Waldorf-inspired charters,” says Oberman. She wants to use stories, poetry, and play to enrich but also to equip children academically so that if they transfer elsewhere they will not be behind.

Teachers, she says, “will not assume the child gets it” but will regularly assess in a Waldorf way. When students write in their Main Lesson books, they will underline a long-A sound, for example, write the word separately, and use it in their own made-up story, all while thinking about, say, a poem they have learned to recite. And where traditional Waldorf does only whole-group instruction, Oberman will do differentiation through centers. “We have the Center of the King, the Center of the Queen, the Center of Angels,” she says.

Parent Aida Salazar, who knew nothing about Waldorf, transferred her six-year-old daughter to Oberman’s school because of the creative approach. “I was really dismayed by all of the worksheets my daughter was bringing home in kindergarten. It seemed an illogical way to get to a child’s mind,” she says.

“An Experiment in the Public Sphere”

Waldorf may be foreign to many parents and educators, but Oberman insists it is “a long-untapped resource in urban school reform.” Can Waldorf’s developmental philosophy and tangible elements—looping, creative hands-on learning, and respect for a child’s innate abilities—change options for poor students?

Robert C. Pianta, dean of the Curry School of Education at the University of Virginia, whose Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS) measures quality instruction in preK–5 classrooms, says research suggests that disadvantaged students struggle as much with self-regulation and relationship skills as with literacy and math skills. But, he cautions, little is known about Waldorf’s effectiveness for these students—or how it can address the critical need for concrete academic instruction.

“We know that kids don’t learn to decode reading and they don’t learn to understand algebra without instruction,” he says. “It strikes me that it is potentially the case that immersing kids in a very intensive and developmentally focused experience may help them build a lot of capacities that will help them in the long term—but we don’t know that.”

“It’s an experiment in the public sphere, and I don’t think anyone right now can predict if it will work,” agrees Bonnie River, chair of Hybrid Programs at Rudolf Steiner College in Fair Oaks, Calif., which focuses on Waldorf teacher training.

River sees more traditional teachers bringing Waldorf approaches into their classrooms. Some training programs are oversubscribed. But River, who has been in education for more than 40 years, has seen the pendulum swing back and forth. Will reformers expect results too quickly? The payoff in Waldorf comes when children reach adulthood, she says. “It may be a little bit too long [for some] to wait.”

Laura Pappano is an education journalist based in New Haven, Conn. She is the author of Inside School Turnarounds: Urgent Hopes, Unfolding Stories (Harvard Education Press, 2010). “Waldorf Education in Public Schools” appeared in the November/December 2011 issue of the Harvard Education Letter.

Waldorf Training in Australia

Waldorf Training in Australia Middle School Science With Roberto Trostli

Middle School Science With Roberto Trostli Full-Time Teacher Education

Full-Time Teacher Education The Journey is Everything

The Journey is Everything Great books for Waldorf Teachers & Families

Great books for Waldorf Teachers & Families Quality Education in the Heartland

Quality Education in the Heartland Summer Programs - Culminating Class Trips

Summer Programs - Culminating Class Trips Train to Teach in Seattle

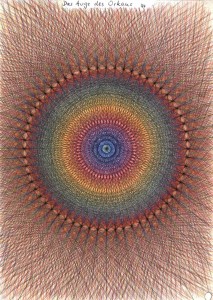

Train to Teach in Seattle ~ Ensoul Your World With Color ~

~ Ensoul Your World With Color ~ Everything a Teacher Needs

Everything a Teacher Needs Roadmap to Literacy Books & Courses

Roadmap to Literacy Books & Courses Apply Today: New Cohort Starts Nov. 2025

Apply Today: New Cohort Starts Nov. 2025 Immersive Academics and Arts

Immersive Academics and Arts Association for a Healing Education

Association for a Healing Education Caring for All Stages of Life

Caring for All Stages of Life Space speaks. Its language is movement.

Space speaks. Its language is movement. Waldorf-inspired Homeschool Curriculum

Waldorf-inspired Homeschool Curriculum Flexible preparation for your new grade

Flexible preparation for your new grade Bay Area Teacher Training

Bay Area Teacher Training Transforming Voices Worldwide

Transforming Voices Worldwide

Bringing Love to Learning for a Lifetime

Bringing Love to Learning for a Lifetime Jamie York Books, Resources, Workshops

Jamie York Books, Resources, Workshops RSS Feeds

RSS Feeds