Waldorf News

When an Adult Took Standardized Tests Forced on Kids

By Marion Brady and Valerie Strauss

A longtime friend on the school board of one of the largest school systems in America did something that few public servants are willing to do. He took versions of his state’s high-stakes standardized math and reading tests for 10th graders, and said he’d make his scores public.

By any reasonable measure, my friend is a success. His now-grown kids are well-educated. He has a big house in a good part of town. Paid-for condo in the Caribbean. Influential friends. Lots of frequent flyer miles. Enough time of his own to give serious attention to his school board responsibilities. The margins of his electoral wins and his good relationships with administrators and teachers testify to his openness to dialogue and willingness to listen.

He called me the morning he took the test to say he was sure he hadn’t done well, but had to wait for the results. A couple of days ago, realizing that local school board members don’t seem to be playing much of a role in the current “reform” brouhaha, I asked him what he now thought about the tests he’d taken.

“I won’t beat around the bush,” he wrote in an email. “The math section had 60 questions. I knew the answers to none of them, but managed to guess ten out of the 60 correctly. On the reading test, I got 62% . In our system, that’s a “D”, and would get me a mandatory assignment to a double block of reading instruction.

He continued, “It seems to me something is seriously wrong. I have a bachelor of science degree, two masters degrees, and 15 credit hours toward a doctorate.

“I help oversee an organization with 22,000 employees and a $3 billion operations and capital budget, and am able to make sense of complex data related to those responsibilities.

“I have a wide circle of friends in various professions. Since taking the test, I’ve detailed its contents as best I can to many of them, particularly the math section, which does more than its share of shoving students in our system out of school and on to the street. Not a single one of them said that the math I described was necessary in their profession.

“It might be argued that I’ve been out of school too long, that if I’d actually been in the 10th grade prior to taking the test, the material would have been fresh. But doesn’t that miss the point? A test that can determine a student’s future life chances should surely relate in some practical way to the requirements of life. I can’t see how that could possibly be true of the test I took.”

Here’s the clincher in what he wrote:

“If I’d been required to take those two tests when I was a 10th grader, my life would almost certainly have been very different. I’d have been told I wasn’t ‘college material,’ would probably have believed it, and looked for work appropriate for the level of ability that the test said I had.

“It makes no sense to me that a test with the potential for shaping a student’s entire future has so little apparent relevance to adult, real-world functioning. Who decided the kind of questions and their level of difficulty? Using what criteria? To whom did they have to defend their decisions? As subject-matter specialists, how qualified were they to make general judgments about the needs of this state’s children in a future they can’t possibly predict? Who set the pass-fail “cut score”? How?”

“I can’t escape the conclusion that decisions about the [state test] in particular and standardized tests in general are being made by individuals who lack perspective and aren’t really accountable.”

There you have it. A concise summary of what’s wrong with present corporately driven education change: Decisions are being made by individuals who lack perspective and aren’t really accountable.

There you have it. A concise summary of what’s wrong with present corporately driven education change: Decisions are being made by individuals who lack perspective and aren’t really accountable.

Those decisions are shaped not by knowledge or understanding of educating, but by ideology, politics, hubris, greed, ignorance, the conventional wisdom, and various combinations thereof. And then they’re sold to the public by the rich and powerful.

All that without so much as a pilot program to see if their simplistic, worn-out ideas work, and without a single procedure in place that imposes on them what they demand of teachers: accountability.

But maybe there’s hope. As I write, a New York Times story by Michael Winerip makes my day. The stupidity of the current test-based thrust of reform has triggered the first revolt of school principals.

Winerip writes: “As of last night, 658 principals around the state (New York) had signed a letter — 488 of them from Long Island, where the insurrection began — protesting the use of students’ test scores to evaluate teachers’ and principals’ performance.”

One of those school principals, Winerip says, is Bernard Kaplan. Kaplan runs one of the highest-achieving schools in the state, but is required to attend 10 training sessions.

“It’s education by humiliation,” Kaplan said. “I’ve never seen teachers and principals so degraded.”

Carol Burris, named the 2010 Educator of the Year by the School Administrators Association of New York State, has to attend those 10 training sessions.

Katie Zahedi, another principal, said the session she attended was “two days of total nonsense. I have a Ph.D., I’m in a school every day, and some consultant is supposed to be teaching me to do evaluations.”

A fourth principal, Mario Fernandez, called the evaluation process a product of “ludicrous, shallow thinking. They’re expecting a tornado to go through a junkyard and have a brand new Mercedes pop up.”

My school board member-friend concluded his email with this: “I can’t escape the conclusion that those of us who are expected to follow through on decisions that have been made for us are doing something ethically questionable.”

He’s wrong. What they’re being made to do isn’t ethically questionable. It’s ethically unacceptable. Ethically reprehensible. Ethically indefensible.

How many of the approximately 100,000 school principals in the U.S. would join the revolt if their ethical principles trumped their fears of retribution? Why haven’t they been asked?

The article above was written by veteran educator Marion Brady, who said he did not name the board member to save him from mean personal attacks by critics. The board member, however, agreed to talk to Valerie Strauss about the experience on the record because he has come to feel very strongly about the issue.

The article above was written by veteran educator Marion Brady, who said he did not name the board member to save him from mean personal attacks by critics. The board member, however, agreed to talk to Valerie Strauss about the experience on the record because he has come to feel very strongly about the issue.

The man in question is Rick Roach, who is in his fourth four-year term representing District 3 on the Board of Education in Orange County, FL, a public school system with 180,000 students. Roach took a version of the Florida Comprehensive Assessment Test, commonly known as the FCAT, earlier this year.

The FCAT, begun in 1998, has been given annually to students in grades 3 to 11 in mathematics, reading, science and writing. It is the bedrock of what is regarded as one of the nation’s most extensive and widely studied school accountability systems. In the last school year, the state began rolling out a next-generation FCAT.

Roach, the father of five children and grandfather of two, was a teacher, counselor and coach in Orange County for 14 years. He was first elected to the board in 1998 and has been reelected three times. A resident of Orange County for three decades, he has a bachelor of science degree in education and two masters degrees: in education and educational psychology. He has trained over 18,000 educators in classroom management and course delivery skills in six eastern states over the last 25 years.

Monday’s post explained how Roach took a version of the FCAT and reached this conclusion in an email to Brady:

“I won’t beat around the bush. The math section had 60 questions. I knew the answers to none of them, but managed to guess ten out of the 60 correctly. On the reading test, I got 62% . In our system, that’s a ‘D,’ and would get me a mandatory assignment to a double block of reading instruction.

“It seems to me something is seriously wrong. I have a bachelor of science degree, two masters degrees, and 15 credit hours toward a doctorate. I help oversee an organization with 22,000 employees and a $3 billion operations and capital budget, and am able to make sense of complex data related to those responsibilities….

“It might be argued that I’ve been out of school too long, that if I’d actuall y been in the 10th grade prior to taking the test, the material would have been fresh. But doesn’t that miss the point? A test that can determine a student’s future life chances should surely relate in some practical way to the requirements of life. I can’t see how that could possibly be true of the test I took.”

Here are some of the highlights of an interview I did with Roach today further exploring his reasons for taking the test and reaching the conclusions that he did.

*Now in his 13th year on the board, he had considered taking the test for a while as he began to increasingly question whether the results really reflected a student’s ability. He was finally pushed to do it earlier this year, he said, after a board meeting at which the chairman listed five goals, and one of them caught his attention for being so unremarkable.

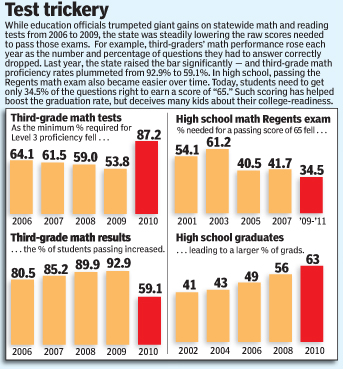

Roach said: ‘He [the chairman] said that by 2013 or 2014, he wanted 50 percent of the 10th graders reading at grade level….I’m thinking, ‘That’s horrible.’ Right now it’s 39 percent of our kids reading at grade level in 10th grade. I have to tell you that I’ve never believed that that many kids can’t read at that level. Never ever believed it. I have five kids of my own. None of them were superstars at school but they could read well, and these kids today can read too.

“So I was thinking, ‘What are they taking that tells them they can’t read? What is this test? Our kids do okay on the eighth grade test and on the fifth grade test and then they get stupid in the 10th grade?”

He asked someone who works at the board to help him take the FCAT but state law only allows it to be taken by students, so it was arranged for him to take a version of it.

He took 60 math questions and a four-part reading test.

How did he score?

On the reading section, he scored 62 percent, a ‘D’ in Orange County. On the math, he said he knew none of the answers but guessed correctly on 10 of the 60.

*Thousands of Florida students with 3.0 or higher grade point averages are denied high school diplomas, Roach said, because they fail at least one portion of the FCAT. Last year, he said, 41,000 kids were denied diplomas across the state — about 70 in his district — and some of them have a 3.0 GPA or better.

*He said he understands why so many students who can actually read well do poorly on the FCAT.

“Many of the kids we label as poor readers are probably pretty good readers. Here’s why.

“On the FCAT, they are reading material they didn’t choose. They are given four possible answers and three out of the four are pretty good. One is the best answer but kids don’t get points for only a pretty good answer. They get zero points, the same for the absolute wrong answer. And then they are given an arbitrary time limit. Those are a number of reasons that I think the test has to be suspect.”

He said he visits schools frequently in his district, including the three high schools (there are 19 high school in the entire county), and talks to principals about this issue. He said they are frustrated that students who they know can read and do math can’t graduate because they can’t pass the test.

Could that mean that all of the teachers in all of the schools are grading too easy?

Roach said “absolutely not.” He knows a lot of the teachers and they aren’t a “soft touch.”

*He said he never brought it up at a board meeting in part because the meetings are publicized and he wasn’t ready until now to publicly discuss it.

*The math section, he said, tests information that most people don’t need when they get out of school.

“There’s a concept called reverse design that is critical,” he said. “We are violating that with our test. Instead of connecting what we learn in school with being successful in the real world, we are doing it in reverse. We are testing first and then kids go into the real world. Whether the information they have learned is important or not becomes secondary. If you really did a study on what math most kids need, I guarantee you could probably dump about 80 percent of math scores and leave high-level math for the kids who want it and will need it.

*His final conclusion on the FCAT:

“They are defending a test that has no accountability.”

This article was prepared from “When an adult took standardized tests forced on kids” by Marion Brady which appeared in the Washington Post Local on December 5 (view at source here) and “Revealed: School board member who took standardized test” by Valerie Strauss which appeared in the Washington Post Local on December 6 (view at source here).

Immersive Academics and Arts

Immersive Academics and Arts The Art of Administration and Leadership

The Art of Administration and Leadership Bay Area Teacher Training

Bay Area Teacher Training Train to Teach in Seattle

Train to Teach in Seattle Association for a Healing Education

Association for a Healing Education Apply Today: New Cohort Starts Nov. 2025

Apply Today: New Cohort Starts Nov. 2025 Grade Level Training in Southern California

Grade Level Training in Southern California Transforming Voices Worldwide

Transforming Voices Worldwide Waldorf-inspired Homeschool Curriculum

Waldorf-inspired Homeschool Curriculum Caring for All Stages of Life

Caring for All Stages of Life Discovering the Wisdom of Childhood

Discovering the Wisdom of Childhood The Journey is Everything

The Journey is Everything Jamie York Books, Resources, Workshops

Jamie York Books, Resources, Workshops Dancing for All Ages

Dancing for All Ages Art of Teaching Summer Courses 2025

Art of Teaching Summer Courses 2025 Quality Education in the Heartland

Quality Education in the Heartland Roadmap to Literacy Books & Courses

Roadmap to Literacy Books & Courses Summer Programs - Culminating Class Trips

Summer Programs - Culminating Class Trips ~ Ensoul Your World With Color ~

~ Ensoul Your World With Color ~ Space speaks. Its language is movement.

Space speaks. Its language is movement. Flexible preparation for your new grade

Flexible preparation for your new grade Waldorf EC Training & Intensives in Canada

Waldorf EC Training & Intensives in Canada Everything a Teacher Needs

Everything a Teacher Needs Bringing Love to Learning for a Lifetime

Bringing Love to Learning for a Lifetime Storytelling Skills for Teachers

Storytelling Skills for Teachers Middle School Science With Roberto Trostli

Middle School Science With Roberto Trostli Full-Time Teacher Education

Full-Time Teacher Education RSS Feeds

RSS Feeds