Waldorf News

Our Hands Belong to Levity

By INGUN SCHNEIDER

A young infant is carried by her mother in a front-pack. I notice that the infant is awake and her little arms hang downwards, hands pulled down by gravity. Another little baby lies flat on her back in a buggy that the mother hurriedly pushes along on a busy sidewalk. The infant is barely visible under the protective hood. I am able to notice that the infant’s hands are raised up above her head and she is moving them gently as she gazes intently at them. She gives the impression of being at peace and thoroughly enjoying getting to know her hands, seemingly removed from her mother’s haste.

Part of my work as a Waldorf educational support teacher is assessing school-age children, either whole classes as part of a class screening or individual children who are having difficulties in school. I find that many of these students’ grasp on the pencil is tense and/or awkward. Then I ask them to do various fine motor activities and notice difficulties with finger differentiation; it’s as if several or all of the fingers work as a unit rather than as separate fingers—which would be more efficient and less tiring. This may sound surprising as students in a Waldorf school do so many activities that involve the hands, from playing the flute or recorder to drawing, knitting and sewing. However, if you look at how these children engage their hands in these activities you can see either a lot of tension or quite loose and almost floppy work. When they draw figures of people they often leave out the hands as if they aren’t quite sure that the hands live at the end of the arms.

Having studied the development of hands for many years, as a physical therapist, interested parent and teacher, I have developed a theory of why so many children (and adults) today have difficulties performing fine motor tasks, including writing by hand. Their hands are unnecessarily tense when writing, they are awkward with the use of tools, and lose interest in crafts, saying that they are not good at it.

My theory has several components. First of all, in order for hand coordination to develop fully, structural alignment in the neck and/or shoulder areas needs to be present. This is because the nerves that innervate the hands go through the shoulders as well as leaving and entering the spinal column at the neck. Sometimes a child’s neck and/or shoulder area (including the collar bone) has been quite compressed during the birth process. This is especially common if the newborn had broad shoulders or if forceps or vacuum extraction was used to help the baby out of the birth canal. If the newborn and young infant is carried in the upright for long periods there is also a possibility of disturbing the alignment of the neck (and shoulder girdle). Of course, parents and caregivers support the immature head and neck, but the infant also has to contribute effort from immature musculature towards maintaining this vertical head position.

My theory has several components. First of all, in order for hand coordination to develop fully, structural alignment in the neck and/or shoulder areas needs to be present. This is because the nerves that innervate the hands go through the shoulders as well as leaving and entering the spinal column at the neck. Sometimes a child’s neck and/or shoulder area (including the collar bone) has been quite compressed during the birth process. This is especially common if the newborn had broad shoulders or if forceps or vacuum extraction was used to help the baby out of the birth canal. If the newborn and young infant is carried in the upright for long periods there is also a possibility of disturbing the alignment of the neck (and shoulder girdle). Of course, parents and caregivers support the immature head and neck, but the infant also has to contribute effort from immature musculature towards maintaining this vertical head position.

On the other hand, when the infant is lying flat on the back or cradled on the side in the parent’s arms the neck muscles aren’t strained before they are ready. The infant can begin to turn the head from side-to-side, lift the head up to look at somebody, or turn toward the breast to nurse, thus gradually allowing the neck muscles to mature. By the time the infant has figured out how to sit up on his own (from lying down), by around 8 to 9 months of age, the neck is plenty strong enough to carry the head upright and able to engage all muscle groups in a balanced way. Then it is time for parents to carry him upright in a front- or back-pack—the baby’s neck muscles are now well-balanced and strong enough to hold the head up with ease. The point I am making is that today we often put our infants into the upright before they are ready; even if the pack has support for the head, in most situations this is not sufficient. Short moments can’t hurt, as long as the birth process didn’t compromise the neck and shoulder girdle too much.

The too-soon-upright situation (before the infant’s musculature is mature enough) also compromises the development of the hands in that the hands tend to dangle down, or, if the baby is older, she may grab part of the pack and hold on to it. In any case when carried or even propped in the upright positions, the baby’s hands do not easily find each other, nor play with the beams of light as they would if lying flat on the back. When in the front- or back-pack the eyes also don’t guide the movements of the hands which is part of the development of eye-hand coordination, basis for the future task of writing, among other tasks. The support that the floor gives the spine (including the neck) when lying horizontal allows the young baby to lift up his arms so the hands end up right above the face. There is little pulling down by gravity as the fulcrum (shoulder joint) is right below the hands, so the hands can play with each other, and the beams of light, for a long time without the arms tiring. Even if the baby is propped only 30 to 45 degrees, the weight of the arms due to the leverage caused by the hands being further from the fulcrum tends to pull the hands into gravity except for short moments of trying to grab something nearby.

Another factor that plays in to the development of the hands is the temporary use of the hands in gravity—as support for the upper body when the baby first pushes up onto the hands while lying on the stomach, soon starts to crawl like a lizard, then creeps on hands and knees. When creeping the hands use a similar gesture to the feet in walking: they swing outward a tiny bit, then forward in the direction of the creeping. The hands’ task is here to connect with gravity so the upper body can be supported enough to allow for locomotion. About three months later the baby has figured out not only how to pull himself up into standing, but also how to balance on the much smaller surface of the two feet and still manage to move forward in the direction he wants to go. Now the hands are truly freed from gravity and can begin to take on their birth right: freely creating, giving and receiving gifts of human kindness.

While the hands are used to support the upper body’s weight they experience pressure on the palms and this seems to be an important factor in furthering the coordination of the hands, for instance for ease of holding the pencil later on. The steady pressure experienced over and over again against the palms as the infant creeps (crawls) around the room actually integrates the palmar reflex. This reflex causes the young infant’s hands to clench as the palms are touched. While this reflex is even subtly present it is difficult for the baby to grasp and let go of objects in a coordinated way. Remnants of this reflexive gesture is seen in so many school-age children’s grasps on the pencil as they write. Imagine the increased tension this causes and how this can lead to a dislike of writing tasks!

While the hands are used to support the upper body’s weight they experience pressure on the palms and this seems to be an important factor in furthering the coordination of the hands, for instance for ease of holding the pencil later on. The steady pressure experienced over and over again against the palms as the infant creeps (crawls) around the room actually integrates the palmar reflex. This reflex causes the young infant’s hands to clench as the palms are touched. While this reflex is even subtly present it is difficult for the baby to grasp and let go of objects in a coordinated way. Remnants of this reflexive gesture is seen in so many school-age children’s grasps on the pencil as they write. Imagine the increased tension this causes and how this can lead to a dislike of writing tasks!

The positions into which we place our infants can thus support or delay the development of the hands. We have our precious hands for giving and receiving, for lifting into levity far above our heads, for communicating via writing and gesture, for making useful and/or beautiful things that we and others can use and enjoy, for playing instruments, and for supporting others in their need.

When considering how to support school children who still have not fully developed their fine motor coordination, it’s helpful to address each area described in the article. I often suggest that parents have the child evaluated by an osteopath or other health practitioner who works with cranio-sacral therapy. This therapy is gentle and non-invasive, yet allows any structural misalignments to be addressed.

Next, I teach the parents how to do a pressure massage of the hands and fingers; it is also helpful to begin at the shoulders and press the arms all the way down to the hands. This pressure is rhythmical, gradually gets firmer, then gradually eases; it gives the child tactile and proprioceptive feedback of the arms and hands, thus allowing for easier use of the hands.

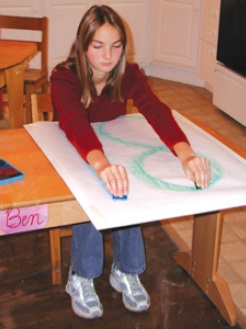

Activities that put weight onto the hands contributes similarly with proprioceptive input while allowing for further integration of any remnant palmar reflex, for instance as the child walks like a crab, kicks the legs up like a donkey or swings through between two desks while the hands carry the body’s weight. Sitting on the upside-down hands in a firm chair as he pushes the body up (like a seated push-up) is another fun way to get weight onto the hands for the school-age child. For all ages kneading dough is fun and rewarding as the baking bread spreads its aroma through the house.

Other interesting proprioceptive activities are: finger-tug-o-war (the child links pointers together and pulls strongly in opposite directions right in front of the body with elbows out to the sides, then moves to the other fingers in turn); Hand Expansion-Contraction and Wool Winding Exercise, both these and other hand exercises are described in The Extra Lesson, see “Suggested Reading.”

Of course, it is helpful to give the student an imagination (or several) to give a picture of the physiologically correct grasp on the pencil. For older students I prefer to explain that the hands and fingers are represented in the brain—that because the thumb and the pointer have more area in the sensory and motor areas of the brain it is, in the long run, much easier to write using these two digits as the main manipulators, with the middle finger supporting them from under the pencil and the last two fingers involved in supporting the hand on the writing surface. This way of grasping the pencil efficiently uses one (of the two) arches of the hands that only humans have (we also have two arches in the foot: longitudinal and transverse). One of the hand arches is seen as the hand is flexed as when all fingers move toward the heel of the hand; it tends to be well developed. The other arch goes from between the middle and ring fingers to the middle of the wrist; this arch is activated when the two last fingers steady the hand while the thumb, pointer and middle fingers manipulate the pencil, chopsticks, paintbrush, or other tool that requires this kind of fine motor movement.

Of course, it is helpful to give the student an imagination (or several) to give a picture of the physiologically correct grasp on the pencil. For older students I prefer to explain that the hands and fingers are represented in the brain—that because the thumb and the pointer have more area in the sensory and motor areas of the brain it is, in the long run, much easier to write using these two digits as the main manipulators, with the middle finger supporting them from under the pencil and the last two fingers involved in supporting the hand on the writing surface. This way of grasping the pencil efficiently uses one (of the two) arches of the hands that only humans have (we also have two arches in the foot: longitudinal and transverse). One of the hand arches is seen as the hand is flexed as when all fingers move toward the heel of the hand; it tends to be well developed. The other arch goes from between the middle and ring fingers to the middle of the wrist; this arch is activated when the two last fingers steady the hand while the thumb, pointer and middle fingers manipulate the pencil, chopsticks, paintbrush, or other tool that requires this kind of fine motor movement.

SUGGESTED READING:

The Extra Lesson and Teaching Children Handwriting by Audrey McAllen.

“Supporting the Development of the Human Hand”, article by Ingun Schneider in The Developing Child: The First Seven Years, Gateways Series Three.

The Hand: How its use shapes the brain, language, and human culture by Frank Wilson.

Ingun Schneider is the course director of the Remedial Education Program at Rudolf Steiner College in Fair Oaks, CA. To learn more about the Remedial Education Program at RSC, just click here.

Transforming Voices Worldwide

Transforming Voices Worldwide Quality Education in the Heartland

Quality Education in the Heartland Bay Area Teacher Training

Bay Area Teacher Training Roadmap to Literacy Books & Courses

Roadmap to Literacy Books & Courses Jamie York Books, Resources, Workshops

Jamie York Books, Resources, Workshops Bringing Love to Learning for a Lifetime

Bringing Love to Learning for a Lifetime Middle School Science With Roberto Trostli

Middle School Science With Roberto Trostli

Space speaks. Its language is movement.

Space speaks. Its language is movement. Great books for Waldorf Teachers & Families

Great books for Waldorf Teachers & Families Waldorf Training in Australia

Waldorf Training in Australia Full-Time Teacher Education

Full-Time Teacher Education Immersive Academics and Arts

Immersive Academics and Arts Everything a Teacher Needs

Everything a Teacher Needs Caring for All Stages of Life

Caring for All Stages of Life Summer Programs - Culminating Class Trips

Summer Programs - Culminating Class Trips Flexible preparation for your new grade

Flexible preparation for your new grade Resiliency and the Art of Education

Resiliency and the Art of Education Waldorf-inspired Homeschool Curriculum

Waldorf-inspired Homeschool Curriculum Train to Teach in Seattle

Train to Teach in Seattle Association for a Healing Education

Association for a Healing Education The Journey is Everything

The Journey is Everything Apply Today: New Cohort Starts Nov. 2025

Apply Today: New Cohort Starts Nov. 2025 ~ Ensoul Your World With Color ~

~ Ensoul Your World With Color ~ RSS Feeds

RSS Feeds