Waldorf News

Drawing with Hand, Head and Heart: Beyond the Right Side of the Brain

The following is an excerpt from the forthcoming book ‘Drawing with Hand, Head and Heart: A Natural Approach to Learning the Art of Drawing’ by Van James. Available September 2013.

The laborer works with his hands, the craftsman works with his hands and his head, the artist works with his hands, his head and his heart. —Francis of Assisi (1182-1226)

Over the past few decades, the theory that postulates dual operations of the brain has become a popular and practical model for understanding the contrasting cognitive functions of the brain and resulting human behavior. The widespread acceptance of this theory has in no small way occurred with the help of mainstream work such as Betty Edwards’ book, Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain.*1 This workbook approach helped to popularize the idea of lateral brain function because it demonstrated the theory by means of observable, practical applications in drawing. If one recognizes right brain activity (artistic, holistic, imagistic, intuitive, simultaneous, present-future oriented) and left brain functions (logical, analytical, verbal, literal, sequential, present-past oriented), one can begin to utilize the appropriate brain operations for specific tasks at hand—in this case, the right brain activity for the purpose of visual thinking to improve one’s drawing. According to this theory, various exercises, such as drawing from a picture that is placed upside-down, can shift the brain (that is one’s perception) into a more artistic, imagistic way of seeing, thus making drawing easier. This theory makes the great mysteries of consciousness, cognition, perception and creativity a bit more accessible and understandable. It is helpful as a starting point for understanding aspects of brain activity and the rich nature of our learning process.

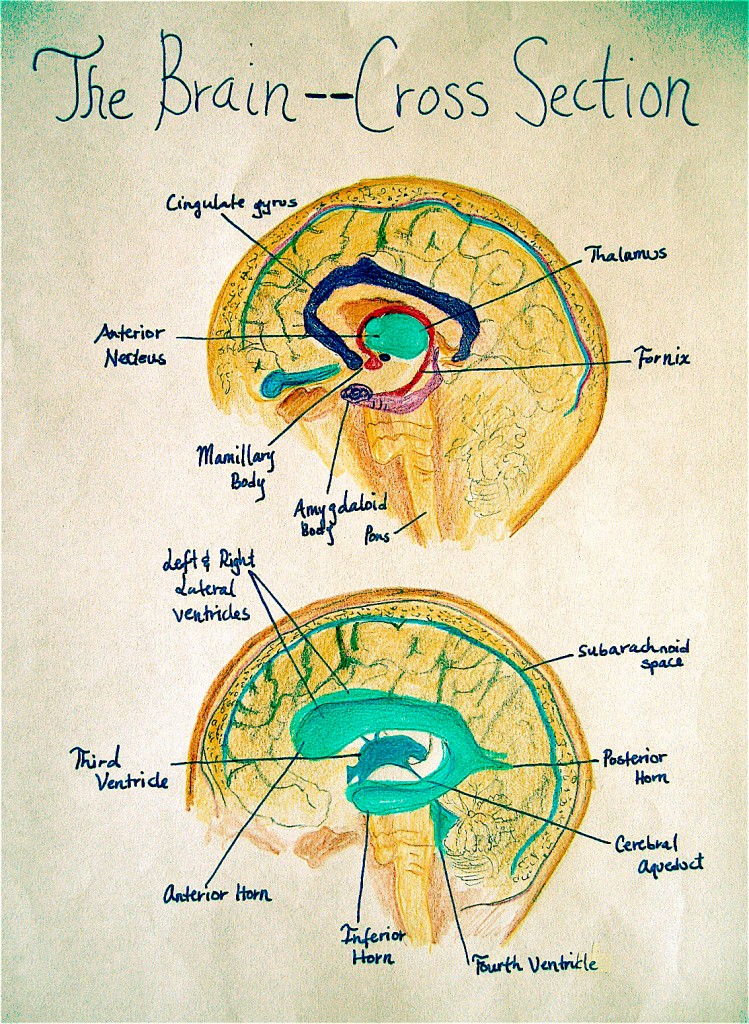

However, twofold, lateral brain functions occur within the wider context of the trifold brain – the so-called reptilian hindbrain (Rhombencephalon—made up of brainstem and cerebellum that deals with involuntary actions and survival mechanisms), limbic midbrain (Mesencephalon—thalamus, hypothalamus, and other brain centers which control emotion, sexuality and memory), and neocortex forebrain or cerebral cortex (Prosencephalon—neomammalian brain involved with muscle function, sense perception, and thought processes).

According to contemporary neurology, up to age three, children learn by way of imitation with the engagement of the reptilian and limbic brains. After age three, there is a growth spurt activating the right hemisphere of the neocortex. The right hemisphere brings intuitive, imaginative, non-linear thinking into action as well as an integrated functioning between the three brain regions. This integrative functioning is responsible for what Joseph Chilton Pearce calls the “magical” relationship a child has to her world, expressed in simple play and untutored creativity.*2 Around eight years of age, children develop foveal focus; the ability to visually scan two-dimensional space. About the age of nine, the left hemisphere of the neocortex begins to function more actively. This hemisphere of the brain gives us abilities for abstraction, objectivity, and linear thought. These latter two events allow a momentous leap in learning as they open the possibility for reading and writing to organically take place, not to mention, continued creative activity.

Fig. 1. The “magical” relationship a child has to her world, is quite observable in her drawings. Around eight years of age, children develop foveal focus; the ability to visually scan two-dimensional space. This drawing was done by a first grader.

These functions of the three brains, as described by neuroscience, are integrated into the still wider nervous system and sense organization, respiratory and circulatory systems, as well as the metabolic and limb systems. This threefold picture of the human organism—the nerve-sense system, where thinking is headquartered; the rhythmic system, where the heart of feelings and emotions live; and the metabolic-limb system, the hands, feet, and gut of our will—which Rudolf Steiner*3 articulated and related so clearly in the context of child development, is naturally important in one’s approach to learning almost anything, especially drawing. It is the basis for speaking of drawing with head, heart and hand—the representative areas of the three bodily systems that serve our capacities for thinking, feeling and will. Thinking, feeling and will are in turn faculties of our soul-spiritual being that allow for understanding of and experiential meeting with the world, as well as our awakening to individuality and selfhood. Ultimately, when we act in the world–when we draw–we do so with the use of both our brain hemispheres, the three brain regions, and the three bodily systems, all of which are active to some degree. When we speak of thinking we generally mean the left-brain activity—reflective, logical thinking. If we act or draw with engaged emotion, with awakened feelings, we engage our right-brain activity and supercede the strictly analytical processes of the left-brain. Naturally, our limb system is engaged when we draw, and this involves the deeper limbic and reptilian brain functions, ie. hand-eye coordination and engaged will impulses. According to this picture we know things with our heads (IQ—intellectual quotient), we feel things with our hearts (EQ—emotional quotient), and we experience things through active doing at a gut level or in our fingertips (WQ—will quotient).*4 All three spheres are forms of knowing and ways in which we learn as human beings.

In teaching and learning any subject it is helpful to keep in mind these three spheres of human activity, recognizing that especially in the child, access to understanding usually occurs from an active doing, simultaneously involving the engagement of feelings, and only later arriving at the formulation of concepts in thinking. When teaching children it is almost always best to first engage the will in an activity that may be experienced inwardly through the feelings, and then be brought to reflection, after the fact, in order to understand it. As a general guideline, before the age of seven to nine, children learn from doing things by example because they learn from imitation not from being told information. One can not tell a child of this age, “please, don’t pick the flowers,” and expect them to follow these instructions if you yourself are constantly picking flowers and demonstrating the opposite behavior. They will always imitate what they see being done around them more than what they are told.

Based on research into children’s brain development, Jane Healy*5 describes this type of first-order learning in children as concrete knowing. Harvard’s Howard Gardener calls it sensori-motor learning and intuitive knowing.*6 By the change of teeth and through puberty, roughly ages seven to fourteen, children learn best through their cognitive feeling, through pictures and symbolic knowing (Healy) or notational learning (Gardener). This is why the arts are such effective learning tools for children of this age. Only in adolescence, between fourteen and twenty-one, does independent judgment and abstract learning (Healy) or formal conceptual knowledge (Gardener) begin to come into its own. In each of these life periods learning can be approached differently in order to be most effective, hygenic and developmentally appropriate.

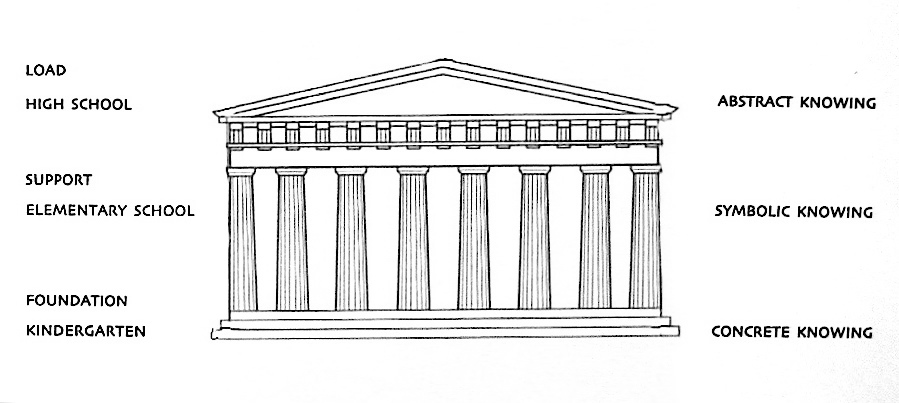

These three stages of knowledge were clearly noted millennia ago by Confucius (551-479 BCE) who declared: “Tell me and I will forget, show me and I will remember, involve me and I will understand.” Telling, showing and involving are the three qualitatively different and progressively deeper forms of knowing: Telling–abstract (thinking), neocortex left-brain function; Showing–symbolic (feeling), neocortex right-brain activity; Involving–concrete (willing), limbic-reptilian and other brain functions. In order to understand the way children, and adults, learn it is important to take a larger view of learning as a process (fig. 2).

Fig. 2. The education of a child is like the architectural elements of a building, requiring a firm foundation, strong supports and walls, and a protective, over-arching roof or load. Hands-on, concrete-intuitive learning provide a foundation for early childhood, while artistic, symbolic-notational learning establishes the columns of support in the middle school years, and the formal conceptual, abstract knowing becomes a kind of roof for the education in adolescence.

How we teach the art of drawing will depend on the age of the child and its particular developmental learning needs: abstract (tell me), symbolic (show me) and concrete (involve me) knowing. As the avenues of hands-on, concrete-intuitive learning provide a foundation for early childhood, and artistic, symbolic-notational learning establishes the walls and columns of support in the middle school years, so the formal conceptual, abstract knowing becomes a kind of capping-off and roofing-over in the architecture of education through the first twenty-one years of life. As foundation, support and load of education are established, all three types of knowing need to become integrated (fig. 3). “Brain plasticity advocates a balanced education of head, heart, and limbs,” according to psychologist and Professor Emeritus of Educational Science, Christian Rittelmeyer. “Only through such “whole” experiences can human beings, through their organic brain rudiments, react to given challenges in a flexible, socially correct, and creative way.”*7

Fig. 3. As hands-on, concrete-intuitive learning, symbolic-notational knowing, and formal conceptual, abstract understanding become established, all three types of knowing need to become integrated and work harmoniously together. Here is a main lesson book drawing by a high school student.

Fig. 3. As hands-on, concrete-intuitive learning, symbolic-notational knowing, and formal conceptual, abstract understanding become established, all three types of knowing need to become integrated and work harmoniously together. Here is a main lesson book drawing by a high school student.

With a comprehensive picture like that of the threefold human being we begin to see what a pivotal place the arts hold in the dynamics of learning; for it is between cognition and action that the arts stand as a great mediator. The arts are a form of knowing-doing/doing-knowing that bridge thinking and will. They imbue thinking with warmth, imagination, originality and enthusiasm, while they strengthen, focus, discipline and give order to the will. Therefore, more and more educational research such as the Visible Thinking, Artful Thinking, Studio Thinking, and other arts integration programs move in this direction of recognizing artistic activity as knowing in action. As Gardener points out: “…artistic forms of knowledge and expression are less sequential, more holistic and organic, than other forms of knowing.”*8 Artistic forms of knowing are the result of repetitive practice on the one hand and on the other, fresh, new delight each time the art is practiced (fig. 4). “The artistic is enjoyed every time, not only the first occasion,” observed Rudolf Steiner. “Art has something in its nature which does not only stir one only once but gives one fresh joy repeatedly. Hence … what we have to do in education is intimately bound up with the artistic element.”*9 Art serves as the balance in education and a bridge to what can make us more fully human in our thoughts, in our feelings, and our deeds.

Fig. 4. Artistic forms of knowing are the result of repetitive practice on the one hand and on the other, fresh, new delight each time the art is practiced. Here are self-portrait studies by 11th grade students using different techniques and different mediums as they tackle the same theme.

“Teachers should love art so much that they do not want this experience to be lost to children,” says Steiner. “They will then see how the children grow through their experiences in art. It is art that awakens their intelligence to full life… [The arts] bring a happy mood into the children’s seriousness and dignity into their joy. With our intellect we merely comprehend nature; it takes artistic feeling to experience it. …[C]hildren who engage in art learn to be ‘creative’ people… they feel their inner nature uplifted to the ideal plane. They acquire a second level of humanity alongside the first.”*10

According to Rittelmeyer,“…research contradicts the intellectual or cognitive interpretation given to it by demands for “brain exercise,” “Baby Einstein,*11 “PISA-Power [Program for International Student Assessment] training,” or similarly uninspiring “neuro-didactic recommendations.” Instead, brain research shows clearly that instructional learning does not lead, in the long run, to “storage” of what has been learned. Rather, sensual experience, happiness and disappointment, and wonder and discomfort are constituent elements of learning and brain development. The ordered multiplicity of experience and association-rich artistic and creative activities, produce an association-rich brain structure, one that in itself seems to be an organic condition for creative thinking and complex emotional cultures. An educational- and socio-economic condition that favors channeled experiences [as in excellerated learning programs, ironically] leads to an impoverishment of the “pathways” of the neuro-logical landscape.”*12

When we make art, when we create drawings, we give expression to our will impulses and urges, our feelings and emotions, our sense experiences, perceptions, imaginations and our thoughts. Art can engage our entire human being, from our dual brain functions and tri-brain system to our threefold bodily organism and triad of soul capacities. Within this picture of our trifold humanity–body, soul and spirit–it is art and the creative process, that serves as the great mediator between our physical-material and our soul-spiritual activity. This is why Steiner suggested: “Art must become the lifeblood of the soul.”*13 Art must become a vital part of our lives, an essential part of our inner life, whatever our profession or lifestyle. And this is why, if we are not to become a robotic thinking machine on the one hand or a willful, desire-driven animal on the other, but are to realize our full potentials, our true gifts, it will be in the sphere of creative capacities, the artist in us, that we may find our universally human attributes. In the end it is essential that we look at human beings as complete organisms in relationship to the world, and not to stop short at considering only brain functions or measurable cognitive processes. After all, we are more than just brains. We are not just our head, we are also hands and heart as well!

….[T]he production of a work of genuine art probably demands more intelligence than does most of the so-called thinking that goes on among those who pride themselves on being ’intellectuals.’—John Dewey (1859-1952)

Notes:

1. Edwards, B. The New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain.

2. Pearce, J.C. The Magical Child.

3. Steiner, R. Study of Man.

4. Although educators acknowledge IQ and in recent years have confirmed an EQ, recognition of a WQ is only just being considered in studies on Studio Thinking (see Hetland, L. and E. Winner, S. Veenema, K. Sheridan. 2007. Studio Thinking: The Real Benefits of Visual Arts Education. Teachers College Press: New York).

5. Healy, J. Endangered Minds.

6. Gardener, H. Intelligence Reframed: Multiple Intelligences for the 21st Century.

7. Rittelmeyer, C. “Advantages and Disadvantages of Brain Research for Education,” Research Bulletin, p. 27.

8. Gardener, H. p. 42.

9. Steiner, R. Study of Man, p.70.

10. Steiner, R. Lecture delivered in Dornach, CH. March 1923. GA36.

11. Walt Disney Company, which holds the copy right on Baby Einstein, Baby Mozart, and Baby Shakespeare, has recently offered consumer refunds on these products because of the unsubstantiated claims that technological tools can advance the education of infants.

12. Rittelmeyer, C., p.17.

13. Steiner, R. The Younger Generation, p. 120

Van James is a teaching artist at the Honolulu Waldorf School and chairman of the Anthroposophical Society in Hawai’i. He is an art instructor at the Kula Makua—Waldorf Teacher Training program in Honolulu and a guest teacher at Rudolf Steiner College in California, and Taruna College in New Zealand. He is the author of several books on culture and the arts, including the forthcoming ‘Drawing with Head, Heart and Hand: Learning the Natural Way to Draw.’

http://www.vanjames.smugmug.com/

Waldorf-inspired Homeschool Curriculum

Waldorf-inspired Homeschool Curriculum Immersive Academics and Arts

Immersive Academics and Arts Space speaks. Its language is movement.

Space speaks. Its language is movement. Summer Programs - Culminating Class Trips

Summer Programs - Culminating Class Trips Bringing Love to Learning for a Lifetime

Bringing Love to Learning for a Lifetime Apply Today: New Cohort Starts Nov. 2025

Apply Today: New Cohort Starts Nov. 2025 Grade Level Training in Southern California

Grade Level Training in Southern California Roadmap to Literacy Books & Courses

Roadmap to Literacy Books & Courses Discovering the Wisdom of Childhood

Discovering the Wisdom of Childhood The Art of Administration and Leadership

The Art of Administration and Leadership Quality Education in the Heartland

Quality Education in the Heartland Middle School Science With Roberto Trostli

Middle School Science With Roberto Trostli Storytelling Skills for Teachers

Storytelling Skills for Teachers Caring for All Stages of Life

Caring for All Stages of Life Everything a Teacher Needs

Everything a Teacher Needs Train to Teach in Seattle

Train to Teach in Seattle Full-Time Teacher Education

Full-Time Teacher Education Waldorf EC Training & Intensives in Canada

Waldorf EC Training & Intensives in Canada Dancing for All Ages

Dancing for All Ages Bay Area Teacher Training

Bay Area Teacher Training Association for a Healing Education

Association for a Healing Education The Journey is Everything

The Journey is Everything Transforming Voices Worldwide

Transforming Voices Worldwide Art of Teaching Summer Courses 2025

Art of Teaching Summer Courses 2025 Flexible preparation for your new grade

Flexible preparation for your new grade ~ Ensoul Your World With Color ~

~ Ensoul Your World With Color ~ Jamie York Books, Resources, Workshops

Jamie York Books, Resources, Workshops RSS Feeds

RSS Feeds