Waldorf News

Saint Michael in the Midst of Everyday Life: Conversation with Waldorf teacher Gudrun Koller

by THOMAS STOCKLI

Translated by Ben and Estelle Emett

To learn about Michael’s fight with the dragon it is sufficient to just awaken every day and meet life openly. There are, however, people who experience this fight in a very intense way because they are in life situations that exist outside of the well-ordered and secure normal daily course of events. They are confronted with exigencies and abysses that other people only experience through literature and the media. There are such people in every country. In my country of Switzerland, in the midst of the prosperous paradise of Zurich, you have only to leave the familiar downtown plaza, ride ten minutes in a streetcar away from the bank district and railroad station – and you find yourself in a completely different world! For instance, you will encounter a schoolhouse with 350 children, almost all of them foreign-born. In this educational milieu more than 90 different languages are being spoken. The children come from a vast number of countries and cultures in the world. Here, Waldorf teacher Gudrun Koller has been doing impressive work for many years. Waldorf pedagogical practices, combined with devoted human involvement and openness to the spirit, are united with the concrete practicalities of life. This woman lives day by day, without fanfare, putting anthroposophical work ethics into practice. All of us have the repeated opportunity to meet something new in our habitual circle; we are all occasionally confronted with a human crisis that can be met with compassion and deeds. The question is: do we heed the “call of Michael,” the summons to engage our own deeds to meet the needs of our fellow human beings?

This conversation with Gudrun Koller began on the playground at recess; she pointed out to us “her children,” a girl and a boy from Sri Lanka, a boy from Bosnia, two boys from Turkey, a boy and a girl from Kosovo, a girl from Somalia, and a boy from Italy. “Aren’t they all just beautiful?” she asked and then told us about the dramatic lives and social conditions of such children, who every year come to her in the introductory class – sometimes fourteen diverse children to a class. This committed educator then related her experiences, quite spontaneously, for three hours, even though that day she had a heavy school schedule. She spoke with a lot of humor and warmth and also with great seriousness and sadness.

This conversation with Gudrun Koller began on the playground at recess; she pointed out to us “her children,” a girl and a boy from Sri Lanka, a boy from Bosnia, two boys from Turkey, a boy and a girl from Kosovo, a girl from Somalia, and a boy from Italy. “Aren’t they all just beautiful?” she asked and then told us about the dramatic lives and social conditions of such children, who every year come to her in the introductory class – sometimes fourteen diverse children to a class. This committed educator then related her experiences, quite spontaneously, for three hours, even though that day she had a heavy school schedule. She spoke with a lot of humor and warmth and also with great seriousness and sadness.

The urgent situation of the children

GK: We teachers never know how to organize to get through the next day because there aren’t enough of us. When someone lasts two years here, it’s a long time.

TS: You yourself have been at this school for thirteen years – how did you manage to do that?

GK: To be honest with you, I once tried to take another position and I received offers. But it never came to that, since I sensed that my place was here – even though I often reach my limits. Without the practice of Anthroposophy I would never have lasted so long.

TS: What essentially does Anthroposophy mean in connection with your work here in a public school? How much do you practice Waldorf education? And how do you experience it in comparison to the activity in a Waldorf school?

GK: I worked for several years in a Waldorf school. It was too confining for me there. Nevertheless, I am quite convinced of the unique significance of Waldorf education and endeavor every day to draw upon these sources. It must, however, be my individual, self-responsible deed how to apply that creatively day to day. I observe the children, and then comes a bold jump into uncertainty. I look for the appropriate pedagogical intuition. In spite of years of experience something completely new comes into being in each situation. The reaction I observe in the children informs me if I have done the right thing. In this way the teaching becomes artistic and full of life. I don’t “missionize” with Waldorf principles. When someone asks me a question, I answer openly. It is important for me that education is really sought out by the children and received with gratitude. The artistic handling of the pedagogical content stimulates the children strongly, both inwardly and outwardly. This is where I must forego the fullness and bring depth to the lesson over an extended period of time. Along with that I try, above all, to activate the secondary senses; otherwise chaos may take over. The excess of sense impressions at home (TV, videos, street noise, and so forth) requires a strong “breathing out” as an antidote which means a coming-to-rest. The ether currents in the whole body must be enabled to flow for education to take place.

TS: How is the situation with the children themselves?

GK: There is a reason why this particular school district was declared a disaster area. With almost a total foreign population here, the children come from the most difficult social conditions. The teaching begins with all of us first having breakfast together. I prefer to pay for that out of my own resources rather than watch the children “breakfast” solely on colas, Red Bull© and other such things. In most cases both parents are working. As a rule, the children are not cared for enough, so that in the first grade they often have a soul development deficiency of three to four years.

GK: There is a reason why this particular school district was declared a disaster area. With almost a total foreign population here, the children come from the most difficult social conditions. The teaching begins with all of us first having breakfast together. I prefer to pay for that out of my own resources rather than watch the children “breakfast” solely on colas, Red Bull© and other such things. In most cases both parents are working. As a rule, the children are not cared for enough, so that in the first grade they often have a soul development deficiency of three to four years.

TS: How is it with the potential for violence – is it really as bad as the media reports?

GK: Worse! The parents are always under pressure to achieve more. By means of signed leasing contracts they live beyond their means. They do not get enough sleep and they eat irregularly. Under these tensions they lose patience and frequently hit and otherwise abuse the children. We can see the results on their bodies when they dress to swim, for example. But actually, little can be done. Even the professional counselors are helpless. The families merely change to another district of the city when it gets too risky, and start all over again. I don’t consider it my job to judge or even call in the police. I am a confidant, the teacher of these children, and have to suffer this powerlessness, too. Only in this way can I give the children a place where at least they can have security during the day along with boundaries and meaning. All the same, the first graders already receive up to twenty-six hours of teaching in a week.

TS: These dramatic destinies of children are heart-breaking! Is this why you came to the “Angel” theme and why you ask for help from the spiritual world?

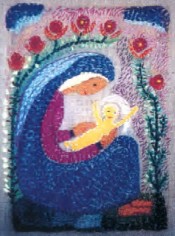

GK: I experience children – and especially the children here – as unusually open to the spiritual world, for the life of the spirit. For them it is very clear: there are Angels, there are guardian Angels, and by means of the embroidery Angels that are months in the making, the children come into inner conversation with these helping guardian Angels.

TS: The majority of the children here are Muslim or Hindu; few of them come from a Christian background. Are there no conflicts here?

GK: Interestingly enough, no! They simply see that there are different names for “God” and “Angel.” I once had a strictly fundamental-educated Muslim youth in my class. When I told stories and legends that involved “God,” he was allowed to call out: “Allah” right after “God.” Actually many of these children are deeply Christian souls (of course, not by confession) who were born in different surroundings, but who came, not accidentally, into a Christian cultural surrounding. Many souls don’t have it easy today to incarnate, and it becomes evermore complicated because of contraception and abortion. But they somehow find the way to religious experiences that belong to them and often purposefully seek a living Christianity. Besides, all religious persuasions are taught in the Bible study.

TS: Is religion such a big subject with these little children?

GK: It is their number one subject and the biggest subject for conversation– sometimes also for arguing. During lessons the following statements and questions are made: “Now, isn’t my grandmother in heaven now?” – “God made the sun, the earth too?” – “Do Angels have teeth?” – “God is always there” – “Where?” – “Around us and in us.” – “Uh-oh! I’d better grow or he won’t have enough room!”

TS: How can you handle these questions?

GK: By questioning the child and then confirming the child’s own feelings. The child becomes satisfied. Then the teaching can go on.

TS: What do you do when there are factions among the parents whose home countries are at war?

GK: Parents can not do what the children can. That is why I have found a special form of “parent evening.” Four times a year all families with siblings, grandparents and relations come into the school on a Friday evening from 6–7 PM. For a half hour the children demonstrate something from their school work. Afterwards I share the school information. In this way enemy nations come peacefully together. The subject is “the children.” During the Gulf War, I could sit with the mothers from enemy nations around a candle. All of us in the circle then shook hands, and when the war was over a Swiss girl donated flowers to replace the candle.

TS: About your Angel embroideries: the echo of your exhibition was overwhelming! You will probably exhibit next year also at the National Expo 2002 (a large Swiss country exhibit) under the project of the Swiss churches entitled “Un Ange passe.” How did all this begin and how is it embedded in the teaching?

GK: The children themselves brought me to it ten years ago through the initiative of a young boy: “There was a dead man in front of our door. The police came. Please draw me an Angel; I want to embroider it.” In the school these children have so many lessons of “instruction” and little time for digestion. In order for the parents to be able to work, blocks were set up with afternoon child care, because the maximum time for lessons for first graders was eighteen hours. So instead we work – usually daily – on these embroidery pictures. The picture’s design is put on burlap with wax crayons and then stretched onto a wooden frame. The work can then begin with thick embroidery needles and many colors. The children are free to choose the kind of stitches. Since embroidery is not part of the school curriculum at this age level, I have to pay for all the materials myself. Actually I came to this project because I was desperately looking for something meaningful for the children to do on these long school days. Otherwise they often get bored, aggressive, and difficult. With an artistic activity like embroidery they become quiet inwardly, and a very beautiful atmosphere in the classroom is created.

GK: The children themselves brought me to it ten years ago through the initiative of a young boy: “There was a dead man in front of our door. The police came. Please draw me an Angel; I want to embroider it.” In the school these children have so many lessons of “instruction” and little time for digestion. In order for the parents to be able to work, blocks were set up with afternoon child care, because the maximum time for lessons for first graders was eighteen hours. So instead we work – usually daily – on these embroidery pictures. The picture’s design is put on burlap with wax crayons and then stretched onto a wooden frame. The work can then begin with thick embroidery needles and many colors. The children are free to choose the kind of stitches. Since embroidery is not part of the school curriculum at this age level, I have to pay for all the materials myself. Actually I came to this project because I was desperately looking for something meaningful for the children to do on these long school days. Otherwise they often get bored, aggressive, and difficult. With an artistic activity like embroidery they become quiet inwardly, and a very beautiful atmosphere in the classroom is created.

TS: How do you find the children of today – the new generation – in comparison to earlier ones?

GK: The children that we have here are very will-oriented; they want to change the world. But because they are often unable to do much, and life is so difficult, they become impatient, unhappy, even furious. That is will power in the wrong place. We then call them “aggressive.” Anthroposophy – meeting and working together with the children

TS: How do you handle being confronted every day with these forces? You said that Anthroposophy also helps – how?

GK: I keep myself focussed inwardly on a picture of the Archangel Michael in which he doesn’t let his gaze be fastened to the abyss, but rather directs his gaze upward toward the spiritual-divine. The destructive powers that surround the children are powerful. The inner pictures that I try to give them in the fairy tale help them to get over the blocking fears, above all trauma from war and violence. Now the question about Anthroposophy– the meeting and working with the children is a path of spiritual schooling. All the elements of the anthroposophical schooling are contained in it, for example the “positivity” exercise. If I criticize and judge a child, then I might as well forget it – the child immediately closes his being from me. Essential to me is to find the reality of the spiritual. Anthroposophy for me is not a schooling structure, but, rather a live being to which I can open myself. Waldorf pedagogy is the instrument for the teaching.

TS: How do you experience the reality of the Angel in your work?

GK: One way is through the children. For myself…? Perhaps I could best experience it as a spiritual flash when in moments of trouble, in moments when I no longer know what to do, I grow beyond myself. For instance, a gang of tough youths in leather jackets wanted to “fish out” and beat up a child in my class. I presented myself before them and with two words could send them away. I sensed that this was not “only me.” Also in daily teaching I rely on such spiritual flashes. I always come to school with a large knapsack, packed with food for the children and also full of teaching ideas. What is then essentially right for the children, however, I have to sense out – and then suddenly an inner certainty is instilled within me – and I experience that my Angel helps me. I grasp the reality of the Angel through my studies in Anthroposophy, but also through my study of art. Recently the theater play “The Angel” by Silja Walther, sister of the author Otto F. Walther, impressed me very much. Such works with supersensible content are unfortunately not performed often.

Waldorf schools: pilot schools in the spirit of the times

TS: Once more back to the Steiner-Waldorf schools: What do you think today, since you know both school systems well, of the Waldorf schools?

GK: It is, of course, very important that there are Waldorf schools, but they live completely out of the personalities who teach there. The Waldorf schools are pilot schools that live with the spirit of the times. In the process of seeking, mistakes can naturally happen. “Busy hands cannot remain clean.” For every Waldorf school teacher I wish that he or she finds the courage to try out something completely new, as dedicated but imperfect human beings! I would like to free the Waldorf schools from all dogma, fixed ideas, and from the fears of adults.

TS: I think you address a very important point here. It is certainly essential for the further development of the Waldorf schools that dogmatic impacts disappear. In past years, nevertheless, much has changed in the Waldorf schools and the atmosphere is much more open. Also, in teacher training we try to go new ways. For it is also important to have the coming generation be involved and full of initiative, to go to school without wearing blinders in order to be open and to learn from the children.

GK: And it is also important that the new teachers don’t have to leave the Waldorf school again because it gets too confining for them. What we practice daily with the children applies also in the College of Teachers. That involves a healthy portion of humor, tolerance, and acceptance in the community as a basis for inner freedom. Student teachers could also get acquainted with such work as we have here, for example. Then they will recognize that Waldorf education can be practiced in different ways and not remain stuck to any one conception. The most important thing is that each one seeks his or her own way; this adds authenticity to the teaching – the children notice it and then try to get involved in the learning.

— Interview was conducted by Thomas Stockli, from Das Goetheanum, No. 51/52/2001

“Saint Michael in the Midst of Everyday Life” is reprinted with kind permission of AWSNA (Association of Waldorf Schools of North America). It was published in the Waldorf Journal Project #5. To see the full journal, just click here.

The Journey is Everything

The Journey is Everything Transforming Voices Worldwide

Transforming Voices Worldwide Everything a Teacher Needs

Everything a Teacher Needs Summer Programs - Culminating Class Trips

Summer Programs - Culminating Class Trips ~ Ensoul Your World With Color ~

~ Ensoul Your World With Color ~ Waldorf-inspired Homeschool Curriculum

Waldorf-inspired Homeschool Curriculum Middle School Science With Roberto Trostli

Middle School Science With Roberto Trostli Bay Area Teacher Training

Bay Area Teacher Training Flexible preparation for your new grade

Flexible preparation for your new grade Waldorf EC Training & Intensives in Canada

Waldorf EC Training & Intensives in Canada Art of Teaching Summer Courses 2025

Art of Teaching Summer Courses 2025 Dancing for All Ages

Dancing for All Ages Discovering the Wisdom of Childhood

Discovering the Wisdom of Childhood Roadmap to Literacy Books & Courses

Roadmap to Literacy Books & Courses Apply Today: New Cohort Starts Nov. 2025

Apply Today: New Cohort Starts Nov. 2025 Bringing Love to Learning for a Lifetime

Bringing Love to Learning for a Lifetime Space speaks. Its language is movement.

Space speaks. Its language is movement. Full-Time Teacher Education

Full-Time Teacher Education Immersive Academics and Arts

Immersive Academics and Arts Train to Teach in Seattle

Train to Teach in Seattle Quality Education in the Heartland

Quality Education in the Heartland Caring for All Stages of Life

Caring for All Stages of Life Storytelling Skills for Teachers

Storytelling Skills for Teachers Jamie York Books, Resources, Workshops

Jamie York Books, Resources, Workshops Grade Level Training in Southern California

Grade Level Training in Southern California The Art of Administration and Leadership

The Art of Administration and Leadership Association for a Healing Education

Association for a Healing Education RSS Feeds

RSS Feeds