Waldorf News

Sherry Turkle: ‘I am not anti-technology, I am pro-conversation’

Sherry Turkle interviewed by Tim Adams

For nearly 30 years now, Sherry Turkle, professor of social psychology at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, has been exploring the effects of digital worlds on human behaviour.

Her books, Life on the Screen, The Second Self and Alone Together, have charted the seductions of “intimate machines”, the advance of social media and virtual realities and the all-pervasive internet, and the effect these things have had on our culture and our lives.

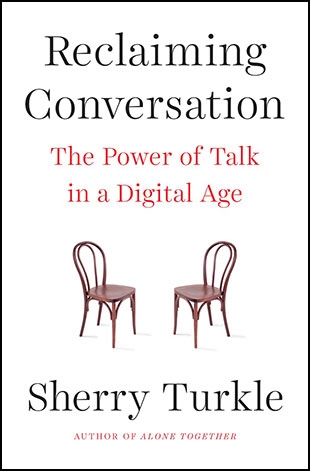

Her latest book, Reclaiming Conversation: The Power of Talk in the Digital Age, is a call to arms to arrest what she sees as the damaging consequences of never being far from email or text or Twitter or Facebook, in particular the impact it has on family life, on education, on romance and on the possibilities of solitude.

Using extensive interviews and half a lifetime of research, she suggests – with reference to the birth of the environmental movement in the 1960s – that we are at a “Silent Spring” moment in our infatuation with life on screens rather than life in the real world, never wholly in one or the other. She measures these effects in a breakdown of empathy between children, in the consequences of increasingly distracted family interaction and a growing need for constant stimulus.

Her antidote is a simple one: we need to talk more to each other. This interview took place by telephone last week.

Sherry Turkle at home in Boston, near MIT. Photograph: Blake Fitch

Sherry Turkle at home in Boston, near MIT. Photograph: Blake Fitch

You have been writing about these issues for a long time now. Has it always felt like a losing battle?

Less so now. In the beginning I thought I was saying things people didn’t want to hear. I think more people see something happening now that they don’t like, but they don’t know what to do about it.

This new statistic seems telling: 89% of Americans admit they took out a phone at their last social encounter – and 82% say that they felt the conversation deteriorated after they did so. It is captured by the story I tell of the young girl saying: “Daddy! Stop Googling! I want to talk to you.”

It is interesting to note that quite a lot of the antipathy towards being “always online” comes not from adults but from children. I suppose we have assumed that these habits would only become more ingrained among people who have grown up with them, but your work shows that is not necessarily the case.

Absolutely not. I was so impressed by kids who said: “I want to raise my children not the way I’ve been raised, but the way my parents think they have been raising me: in a house of conversation.” That was stunning.

But what if children haven’t had any experience of sitting around a dinner table, or of talking to their friends without a iPhone to hand? How do they know what they are missing?

That’s the danger. But I believe that we are resilient. I like the study that shows that after five days away at camp without connections you see the empathy markers among children rising. The ability to recognise the emotions of somebody in a video or a story go right back up. I believe we are wired to talk. It is a Darwinian thing.

Easy to pick up, hard to put down… Photograph: Richard Levine/Demotix/Corbis

I guess we are also wired for novelty and distraction…

Yes. But I feel we have now created an environment that will distract us to distraction. My recipe does not involve my giving up my phone. It’s too useful. But it means not using it on occasions like this when I am trying to give you my full attention. The human voice occupies a lot of bandwidth if you listen to it properly. If I was also texting, you would not be getting a sense of me.

I’ve worked in a newspaper office for 20-odd years. In that time, like all offices, it has become much quieter. Everyone used to be on the phone, now they are often emailing. Do you think something is lost in that?

If you sent me 10 email questions, you would get very different answers from me. Typing is not the same as talking. Students increasingly say they don’t want to see me in person, they just want to email me. When I ask why, they basically say they want to get their questions perfect, so I can make my answers perfect. They want my perfect to meet their perfect.

Email allows us to give the press-release version of ourselves?

Yes. But that is not who we are. It’s an algorithmic view of life. Who ever loved learning because they asked the professor a perfect question and the professor gave a perfect answer?

Certainly when I think of teachers who inspired me I couldn’t tell you precisely what they said, but I can certainly remember the tone and the circumstances in which they said it.

Exactly. It’s the fact you were there and thought: could I someday be like them?

You came to some of this understanding quite prophetically. I mean you were writing about the lure of digital worlds back in the 1980s.

I wrote my first book really in an effort to get people like me, humanists and anthropologists and psychologists, to look at these things with an open heart. That was about at the beginning of sociable robotics, the creation of machines that pretended to care about you. That appeared to love you.

The other big development was devices with the ability to distract you all the time. I was very positive on the whole about machines that you physically went to. That you had to pull up a chair to. But once these things were with you all the time, I really wanted to study how the world changes with that possibility.

Tablet computers in the classroom: not such a good thing for child development? Photograph: Alamy

There are obviously huge commercial interests in that shift. And despite widespread understanding of the implications of it, of the end of privacy and so on, it seems most people believe it a price worth paying.

I want to be part of the change. I have met engineers and people in the industry who have said, you know, there is also money to be made in allowing you to have time off from your phone. The question is, how high do the costs of not doing that have to be? If you begin to see spikes in developmental issues? When people forget how to talk to each other?

You are not immune to the pull of these devices yourself.

I feel all of it. I have to fight the impulse to use my phone as an alarm clock rather than leaving it in another room. If I don’t I will wake up in the middle of the night and think: I’ll check my messages. Or the number of my book on Amazon. If I start checking my phone at two in the morning I suddenly find it is four in the morning and I have to get up in two hours.

Perhaps writers crave distraction more than most.

Perhaps. It’s like Zadie Smith acknowledging Freedom, that program that lets you turn off Wi-Fi, for allowing her to finish her last book. People really struggle. I have interviewed several people who say they now have to go to remote country cabins to get any concentrated work done. Then they find themselves driving around the neighbourhood trying desperately to find an unlocked Wi-Fi signal. Knocking on doors.

The scary thing about that is that these people are adults. Children have much less opportunity for self-control.

Yes but the thrust of my argument is not that we have a device that has constant conversation on it. It is with the fact that there are no limits on that. It is with the father who checks his email while giving his two-year-old a bath when he used to play with her. Those are the lost conversations I am worried about. The fact is we need to design around our vulnerabilities.

But there is no sense that the corporations that make billions of dollars from these habits are going to adopt that idea willingly.

I like to look at the food industry and how it has evolved. My mother, when I was growing up, adored me but she also fed me white bread, tinned vegetables, potatoes that she made from flakes, TV dinners. It was a profit-centred industrial kind of machine that led her to do that.

But a young mother today – if that was what she was feeding her child – you would know she was not with the programme.

How did we turn that around? It certainly wasn’t because the food industry said “Ooops!” It came from people seeing the effects of this diet. And that is how I think this will go also. There is study after study saying the same things: talk to each other, experience solitude, experience boredom.

Boredom is your imagination calling to you. I think it will happen slowly.

The lure of the sociable robot and the digital future, once so appealing, appears to have worn off. Photograph: Allstar

I suppose in the case of nutrition there are physical effects that can be measured, though; isn’t this more intangible?

I’m not sure the effects of not talking are hard to measure. The interviews that I did in business settings, people said people come to them for jobs and literally don’t know how to have a conversation.

I mean if you take a baby and put them on a baby bouncer that has a slot for an iPad, instead of taking time to have eye contact and reading to them, and then they go to a school where most of their instruction is on a screen, why be surprised when they show up as sixth-graders [those in the first year of secondary school] looking down at the floor and being unable to speak?

I came across many kids who are set homework on tablets but can’t concentrate on reading it until they print it out. I am sympathetic to that. I know for a fact that it’s hell to try to read complicated things on a machine that also gives me access to every other thing in my life. We are asking kids to read homework on a device that also gives them access to everything that matters to them: Facebook.

It’s sad to witness that struggle.

How did you negotiate these things with your own daughter? I have two daughters, 16 and 12, and my experience is that you have to choose your battles…

We did the sacred space thing. And it mostly worked. No computers or phones in the kitchen, at the dining table, or in the car. Those are the places I think where you create family space. The car is very important.

I don’t think it works if you talk about set hours or whatever. And it is of course crucial that you apply the same sacred space rule to yourself as to them. The issue is not that your child loves using their screen to write. The issue is that they should not be doing it when they are talking to you. I never friended my daughter on Facebook; that wasn’t our space to share things. Instead I had dinner with her pretty much every night.

I am not anti-technology, I am pro-conversation.

Can you see this becoming a movement?

I do see it. Every time you go and see a doctor and he looks at a screen and not at you, for example, this movement is strengthened. In business the research on how useful conversation is to the bottom line will make it a movement.

Do you encounter hostility to that message?

Much less than five years ago. When I wrote my last book, Alone Together, people were angry. The dominant emotion I encountered was irritation: “Give it a rest.”

Isn’t that a classic symptom of addiction – people don’t want to be told that the thing they are in thrall to is harming them?

I wouldn’t use that metaphor. If you are addicted to heroin you have to give it up completely, go cold turkey. Here it is a different assignment. I am not planning to give up my phone. I just need to know what it is good for.

Are you hopeful those habits will catch on?

I am not Pollyanna and deluded. If people start to buy the idea that machines are great companions for the elderly or for children, as they increasingly seem to do, we are really playing with fire. I think the stakes are very high. But the good thing is we don’t have to invent anything to turn it around. We already have each other to talk to.

Reclaiming Conversation: The Power of Talk in a Digital Age is published by Penguin.

From theguardian.com.

Bay Area Teacher Training

Bay Area Teacher Training Jamie York Books, Resources, Workshops

Jamie York Books, Resources, Workshops Apply Today: New Cohort Starts Nov. 2025

Apply Today: New Cohort Starts Nov. 2025 The Journey is Everything

The Journey is Everything Full-Time Teacher Education

Full-Time Teacher Education Association for a Healing Education

Association for a Healing Education Waldorf-inspired Homeschool Curriculum

Waldorf-inspired Homeschool Curriculum The Art of Administration and Leadership

The Art of Administration and Leadership Discovering the Wisdom of Childhood

Discovering the Wisdom of Childhood Waldorf EC Training & Intensives in Canada

Waldorf EC Training & Intensives in Canada Immersive Academics and Arts

Immersive Academics and Arts Caring for All Stages of Life

Caring for All Stages of Life Grade Level Training in Southern California

Grade Level Training in Southern California Everything a Teacher Needs

Everything a Teacher Needs Summer Programs - Culminating Class Trips

Summer Programs - Culminating Class Trips Middle School Science With Roberto Trostli

Middle School Science With Roberto Trostli Quality Education in the Heartland

Quality Education in the Heartland Dancing for All Ages

Dancing for All Ages Art of Teaching Summer Courses 2025

Art of Teaching Summer Courses 2025 Space speaks. Its language is movement.

Space speaks. Its language is movement. Storytelling Skills for Teachers

Storytelling Skills for Teachers Roadmap to Literacy Books & Courses

Roadmap to Literacy Books & Courses Flexible preparation for your new grade

Flexible preparation for your new grade ~ Ensoul Your World With Color ~

~ Ensoul Your World With Color ~ Train to Teach in Seattle

Train to Teach in Seattle Transforming Voices Worldwide

Transforming Voices Worldwide Bringing Love to Learning for a Lifetime

Bringing Love to Learning for a Lifetime

RSS Feeds

RSS Feeds