Waldorf News

What happens when you mix math, coral and crochet? It’s mind-blowing: How two Australian sisters channeled their love of STEM and coral reefs into the most glorious participatory art project

By Rebekah Barnett

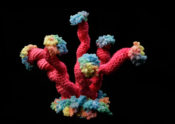

“We’re used to thinking about math as something you have to learn through textbooks and equations,” says science writer Margaret Wertheim. But through their Institute for Figuring, she and her sister, Christine, have made it their mission to help people see math and science differently by finding hands-on ways to engage them with abstract concepts. Among their efforts: the mesmerizing Crochet Coral Reef. Why crochet and coral? Many reef organisms are living examples of a complicated form of geometry, and crocheting their shapes allows people to work with geometric principles in a tactile way.

Started in 2007, the Wertheims’ reef grew out of the Australian sisters’ many interests: their passion for math and science; shared fondness for crochet; love of their country’s Great Barrier Reef and desire to highlight global warming’s impact on coral reefs and oceans in general. Today the Crochet Coral Reef is made up of thousands of handcrafted corals and reef organisms — created by a network of contributors — that Margaret and Christine, an artist and professor, have curated into displays that have been exhibited worldwide. Here, Margaret Wertheim shares some of the amazing organisms created for their project and shows how their crocheted reef has grown and evolved over the years.

Math like you’ve never seen it before

Many reef organisms, like nudibranches, sponges and kelps, possess structures that embody a head-scratching form of geometry called hyperbolic geometry. Hyperbolic geometry was discovered in the 19th century, revolutionizing the field of mathematics and eventually paving the way for Einstein’s general theory of relativity. Yet physical and durable hyperbolic models that would allow people to explore hyperbolic geometry in a tactile way did not exist until 1997 when Dr. Daina Taimina, a mathematician at Cornell, realized forms could be made using crochet. To create this 18-inch-long hyperbolic shape, artist Siew Chu Kerk followed Taimina’s formula pretty exactly, says Wertheim, “which is crochet n stitches, increase one and then repeat that ad infinitum.”

They’re more than hyperbolic

The Wertheim sisters first called their project the Hyperbolic Crochet Coral Reef, but they quickly realized that in order to capture the full beauty of this special ecosystem, they’d need to include organisms that lacked hyperbolic features. Some reef creatures have only a few hyperbolic parts (and some display no hyperbolic geometry at all). For example, the curlicues at the end of this octopus-like creature’s tentacles and its center are hyperbolic shapes, Wertheim says, but other elements of this organism, like the long parts of the tentacles, are not. Helen Bernasconi, an early contributor to the project and a rug weaver by trade, sheared, spun and dyed wool from her own sheep to make this piece.

Bringing art into the equation

While this delightful pastel creation, made by Vonda N. McIntyre, is a crocheted replica of fingerling coral, not all contributors hew so closely to reality. This was a deliberate artistic choice on the part of the Wertheim sisters. “Just as a painter is painting a landscape and doesn’t want to produce a photocopy of it, we want to be like Van Gogh, Cézanne or Monet,” says Wertheim. “We’re trying to look at the world and produce a beautiful aesthetic version.”

A branching network of makers

This kelp piece shows the technical skill of Ildiko Szabo, a theater costume designer and another of the project’s earliest contributors. After she and Christine came up with the idea of such a reef, Wertheim recalls, “I put something up on [the Institute of Figuring’s] website saying: Is there anyone else who’d like to join us in this quixotic project at the intersection of handicraft, mathematics and environmentalism?” To their surprise and delight, they began receiving crocheted objects in the mail from people they’d never met. Years later, Szabo remains one of the reef’s 40 to 50 core contributors. Altogether, nearly 100 people — whose ranks include sci-fi writers and computer programmers — are behind the roughly 10,000 pieces that make up the reef.

Small pieces, major work

Rebecca Peapples created this beaded piece (which is attached to the center of the white star in the next photo) using a traditional beading stitch called the herringbone. While only around three inches in length, Wertheim estimates that Peapples spent around 10 to 15 hours to produce it (pieces in the reef range in size from a few inches to a few feet). The white star, about the size of a human hand, probably took up to 30 hours to make; some pieces have taken hundreds of hours. “One reason why I think the reef is powerful is because everybody can tell when they walk in the door there has been a huge commitment of time,” she says.

The delicate fusion of craft and science

This piece, knitted by Anita Bruce using a fine coated wire, was her attempt at using handicraft to mimic the evolutionary process. Bruce began with a simple shape, like the thin pods sticking out from the angles of the star, and then let a random number generator determine how to continue to create the shape. This Darwinian echo is something that Wertheim sees across the Crochet Coral Reef as a whole. “Every [contributor] starts by learning how to do a simple hyperbolic structure,” she explains, a shape she compares to a simple cell. But just like evolution, crocheters go from the simple to ever-more complicated structures.

Our future is plastic

In addition to warming ocean temperatures, another major threat facing marine ecosystems is plastic. After starting the reef, the Wertheim sisters learned about the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, and they responded with the Toxic Reef, a collection of organisms — like this jellyfish — that were crocheted or knitted out of plastic. Learning about the garbage patch also inspired the Wertheims to keep all of their domestic plastic trash for four years, accumulating a total of 440 pounds. They contained this trash in a net, and it’s now displayed as part of the reef under the name “The Midden.” Common reactions from visitors are amazement and disgust. To the latter group, Wertheim says, “If you don’t like it, think about it — the yarn reefs represent the natural beauty of nature that’s rapidly disappearing, and the plastic represents the future of what humanity is creating.” This jellyfish was crocheted from plastic bin-liners by Wertheim.

Death’s white beauty

These stunning pale pieces were made by Evelyn Hardin, which Ann, another Wertheim sister, organized into a long grove. While the monochromatic grove is enchanting to look at, it illustrates a deadly ocean phenomenon: coral bleaching. When corals become stressed by factors like acidification and rising temperatures, they expel the symbiotic zooxanthellae algae that gives them their bright color and turn bone-white. The algae also help provide food for corals, so without them, they become more and more vulnerable and can die. The Wertheim sisters have curated two reefs, the Bleached Reef and the Bleached Bone Reef, to spotlight this increasingly urgent problem (in November, scientists announced the largest coral die-off in the Great Barrier Reef ever recorded). Should coral reefs perish altogether, Wertheim believes the crocheted reef would stand as an extraordinary testament to the beauty of the reefs — and an extraordinary indictment of humanity for destroying them. “It would become like a museum artifact of yet another thing that humans, with our inability to limit ourselves, have wiped off the face of the Earth,” she says.

A playful, pastel reef

While the Crochet Coral Reef conveys serious messages about the degradation of the marine ecosystem, the sisters also want the reef to be playful and engaging. One example: these tube worms, crafted by Szabo in a vibrant mix of pastels and neons. The sisters hope to raise awareness about climate change through positive means rather than messages of doom and gloom. Upon seeing their reef, Wertheim says, “people’s first reaction is usually to laugh, and we want that.” That playful spirit helps bring visitors and crocheters into a conversation “about these very difficult, destructive processes going on where reefs are in danger of being wiped out.”

The power of the people

Besides the reefs curated by the sisters, their project has expanded to encompass dozens of community reefs in 40 cities around the world from Oslo to Adelaide, from Fukuoka to San Antonio. They are in a number of different of places, including the Smithsonian in Washington, DC, prisons, and homes for the disabled. This collection of organisms, all created by Dagnija Griezne, is just one section of a Latvian community reef, a project spearheaded by artist Tija Viksna. Women from all over the country contributed, as well as more than 600 schoolchildren. One common thread that links all the reefs in the project — whether it’s the Wertheims’ curated displays or the community reefs — has been their collective nature. “You get an artwork that’s much, much greater than any individual artist could’ve achieved by themselves,” says Wertheim. Students, faculty and staff at the University of California Santa Cruz are crafting the latest community reef, and these human-made ecosystems keep spreading. “We never quite know who’s going to do it next,” adds Wertheim.

All photos are from the Crochet Coral Reef project by Margaret and Christine Wertheim and the Institute for Figuring. To learn more about exhibitions, satellite reefs and contributors, go to crochetcoralreef.org

The Journey is Everything

The Journey is Everything Apply Today: New Cohort Starts Nov. 2025

Apply Today: New Cohort Starts Nov. 2025 Everything a Teacher Needs

Everything a Teacher Needs Middle School Science With Roberto Trostli

Middle School Science With Roberto Trostli Full-Time Teacher Education

Full-Time Teacher Education Quality Education in the Heartland

Quality Education in the Heartland Great books for Waldorf Teachers & Families

Great books for Waldorf Teachers & Families

Transforming Voices Worldwide

Transforming Voices Worldwide Resiliency and the Art of Education

Resiliency and the Art of Education Waldorf EC Training & Intensives in Canada

Waldorf EC Training & Intensives in Canada Waldorf-inspired Homeschool Curriculum

Waldorf-inspired Homeschool Curriculum Bringing Love to Learning for a Lifetime

Bringing Love to Learning for a Lifetime Space speaks. Its language is movement.

Space speaks. Its language is movement. Bay Area Teacher Training

Bay Area Teacher Training Caring for All Stages of Life

Caring for All Stages of Life Jamie York Books, Resources, Workshops

Jamie York Books, Resources, Workshops Immersive Academics and Arts

Immersive Academics and Arts Train to Teach in Seattle

Train to Teach in Seattle ~ Ensoul Your World With Color ~

~ Ensoul Your World With Color ~ Association for a Healing Education

Association for a Healing Education Waldorf Training in Australia

Waldorf Training in Australia Roadmap to Literacy Books & Courses

Roadmap to Literacy Books & Courses Summer Programs - Culminating Class Trips

Summer Programs - Culminating Class Trips Flexible preparation for your new grade

Flexible preparation for your new grade

RSS Feeds

RSS Feeds